(This is the 2nd part of my notes from the International Conference on Infectious Diseases [ICID] – see 1st part on Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus [MERS-CoV] here…or scroll down to the next post)

Zika virus was on everybody’s mind at ICID and there were a lot of very insightful presentations from those who are dealing with the current situation in Brazil.

A brief history of Zika

Firstly, it is important to acknowledge that, just like MERS-CoV, Zika has been around for longer than most people think. It was originally discovered in the Zika Forest of Uganda in 1947 in a sentinel Rhesus monkey. The following year, it was found in Aedes africanus mosquitoes. It was not until 1952 that the first human cases emerged.

In the 60 years since its discovery, evidence was found showing that Zika was distributed throughout West Africa and Asia (India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan). Further analysis of the virus differentiated three different strains: East African, West African and Asian. During that time, few cases had been identified, however, scientists recognized early on the difficulties in differentiating Zika from other similar viruses such as chikungunya or dengue fever. In general, symptoms of Zika have been mild, including fever, skin rash, arthropathy and conjunctivitis.

Outbreaks in French Polynesia & Brazil – New effects of Zika on newborns

The first outbreak that put Zika on the map startedin 2013 in several islands of the Pacific, including French Polynesia. More serious complications from infection with the virus were noted, such as neurologic symptoms, Guillain-Barré syndrome and possible congenital malformations.

Not long after, in Spring of 2014, increased cases of rashes started appearing in Brazil. Zika was not on the list of potential causes, because many local diseases cause similar clinical appearance (such as dengue and chikungunya). To complicate things, several of the affected patients tested positive for dengue. Over time, it became apparent that people affected were not showing all the classical signs of dengue. A couple of months into the outbreak authorities began to look elsewhere to explain what was happening in Brazil – and Zika was found. This was the first time the virus was identified in the Americas.

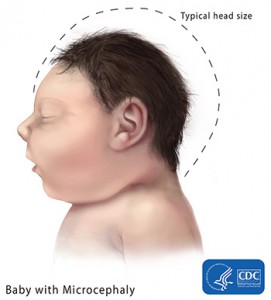

The situation in Brazil revealed a concerning new development. In areas where Zika was spreading, mothers started giving birth to children with microcephaly.

Much discussion has been made about the link between Zika virus infection and microcephaly. Some have claimed that the congenital abnormalities could have been caused by something else, such as a specific pesticide that was used around the same time microcephaly clusters appeared. Our speakers at the conference seemed to challenge that idea, as microcephaly cases were seen in areas where the pesticide was not present. In addition, more research into the issue revealed the presence of Zika virus in the brains of newborn with microcephaly. In fact, looking back to the 2014 outbreak in French Polynesia showed that similar congenital abnormalities likely occurred as well. Some have also put forth the idea that the strain involved in the Brazil outbreak is related to the one from French Polynesia.

Currently, the Zika outbreak that started in Brazil has spread to other countries of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Why is Zika changing?

So why is Zika changing all of the sudden? How did this new feature of microcephaly appear? The epidemiologic triad can help elucidate part of these questions. The triad describes three major components of a disease: the agent (pathogen), the host or the environment. Any alteration to these three pillars can change the epidemiology and characteristics of an illness.

The pathogen. We knew that Zika already could affect the neurological system of newborn from the 2014 outbreak in French Polynesia. It is possible that, through natural mutations, the virus acquired genes that made it more efficient at infecting the foetal brain, leading to an increased rate of microcephaly.

The host. Because Zika has been around for decades in Africa and Asia, populations in these areas have already been exposed to the virus and developed an efficient immune response to it. In other parts of the world however, humans and animals have never been infected with the disease and are thus, not protected (i.e. naïve). In the case of Zika in Latin America, the disease may cause more severe symptoms after infection because the local populations are naïve. This has been seen with the spread of another mosquito-borne disease into the Americas: West Nile virus.

The environment. Spreading into a new environment can shift a particular disease’s ecology. In Latin America, different species of mosquitoes may be more efficient at spreading Zika. The virus may also infect different species of animals where it can multiply at a faster rate than in other parts of the world.

Any part of the epidemiologic triad can help explain why Zika behaves differently in Brazil compared to other countries where it has been present for a while. It is likely that all three components of the triad play a part in the fast spread of Zika through the Americas.

Zika, Dengue, Chikungungunya – It’s a mess to tell them apart

One of first challenges in identifying the Zika outbreak in Brazil was the fact that the disease shares many similarities to other illnesses commonly seen in that part of the world, such as dengue and chikungunya. Many symptoms overlap between these three viruses, such as rash, headache, fever or conjunctivitis. Physicians have to look at them very closely to be able to start differentiating these diseases clinically.

To complicate things, dengue and chikungunya are spread by some of the same mosquitoes that transmit Zika (Aedes aegypti and A. albopictus) and it is likely that people become infected by more than one virus.

Finally, both dengue and Zika both belong to the same family (Flaviviruses), which means their genetic code is closely related and few diagnostic tests can differentiate them (until now, tests that could tell Zika and dengue apart were not in high demand).

Speakers at ICID made several recommendations to start narrowing down which of those three diseases could be present in an infected patient:

- Has there been any deaths? Of all three diseases, dengue is the deadliest. If death is not a prominent feature of an outbreak, then dengue is the least likely culprit.

- Is there any fever? Dengue can cause moderate fever; chikungunya is usually characterized by high fever. In Zika, fever may be absent.

- Is there any rash? In the case of dengue, a rash usually appears at 7 days after infection, whereas a rash from Zika usually appears within 2-3 days. In addition, these rashes can be more severe, very pruritic and non-responsive to medications.

- What are the characteristics of the pain experienced by the patient? All three diseases can cause headache and joint pain. However, with dengue, joint pain is usually present during episodes of fever. Chikungunya can cause a very severe and debilitating joint pain compared to Zika, where pain is more limited and cyclical.

- Is there edema? Edema from Zika virus is usually cold (i.e. not related to inflammation).

- Is there conjunctivitis? Patients infected with Zika virus often have conjunctivitis. Chikungunya causes occasional conjunctivitis, while this symptom is not usually a feature of dengue.

- Is there bleeding? Dengue can cause a hemorrhagic syndrome while the other two viruses don’t.

Zika is scary…but so are other mosquito-borne diseases. The answer has always been: mosquito control

Zika has been around for more than 60 years and barely made the news until now, mostly because of the newly recognized effect of microcephaly. Unfortunately, along with the increased coverage can come many misconceptions. Zika is serious, but it is rarely fatal. In comparison, dengue is deadlier, and chikungunya can cause long-lasting debilitating joint illness. In fact, the mild nature of Zika, coupled with its congenital effects is the most concerning aspect of the disease. Many people may not be aware they are infected and could pass on the virus to their unborn child.

The lesson to learn from this current outbreak is that mosquitoes be vectors for several serious diseases. These include Zika, dengue, chikungunya discussed in this post, but also yellow fever, West Nile virus, malaria and more. Because of pressures to the pathogen, host, or environment, it is likely that these diseases will continue to change. While today we focus on Zika, tomorrow’s mediatized disease may be yellow fever, or even a new emerging disease.

Regardless of the disease in the spotlight – recommendations have always remained the same: mosquito control to prevent bites. This will decrease the likelihoods of infection from Zika, dengue, chikungunya or any mosquito-borne disease that we don’t know exists yet.

More information

World Health Organization (WHO) – The origin and spread of Zika

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – Dengue frequently asked questions